Article by MH Hassan

If a woman lodges an information alleging that A has raped her, then by showing or supplying A with the first information, he is given the opportunity to explain the circumstances; he may show that there was in fact no rape and the woman consented to the whole thing.

Similarly, if A is accused of murder in a first information, he may explain that he was elsewhere at the time or show circumstances that the act was an accident. Now if A did not see the information, he would not be able to vindicate himself or to meet the various particulars alleged in the first information.

The illustration is not mine, but that of Syed Othman FJ in Husdi v Public Prosecutor [1979] 2 MLJ 304.

In that case, the federal court judge, sitting in a criminal revision in the high court, expressed his view that the common law right of an accused to inspect the first information arises from the duty of the police to inform the accused the reason for his arrest, so as to enable the accused, if he so wishes, to explain his conduct as alleged in the first information, which, on the face of it, constitutes an offence.

By the way, the first information (or what is commonly known as the first information report – FIR) is otherwise known as the police report. It is a public document as defined by section 74 of the Evidence Act 1950 (EA).

Consequently, a person having a right to inspect the document must be given on demand a copy of it on payment of the prescribed fees as provided by section 76 of the EA. So, if A is the person named in the police report by the woman alleging rape, then A has a right to inspect the report.

He should be given, on request, a certified true copy of it on payment of the fees. A’s right to inspect is a right based on the common law which accrues right to a person to have access to a document in which he has an interest.

Such inspection, according to the federal court in Anthony Gomez v Ketua Polis Daerah Kuantan [1977] 2 MLJ24 recognising the common law right to inspect, is necessary for the protection of his interests.

Indeed, this right has a constitutional colour to it. According to Syed Othman FJ in Husdi, the right of an accused person to the FIR is nothing more but a consequence of his right to be informed as soon as may be of the grounds of his arrest under Article 5(3) of the Federal Constitution.

Now apart from the above, in criminal practice, the FIR is a document usually made available to a person having interest in it upon request and without much ado. As a matter of fact, in accident cases, the police do supply a certified true copy of the FIR on payment of the prescribed fees not only to the maker but also to other persons affected.

In view of the above, I find statements suggesting that a police report will not be made available to a person having interest it because he or she has not given statements to the police disturbing.

It cuts through the honest and selfless efforts by civil society at promoting public awareness of and providing public education relating to rights. Equally disturbing are statements suggesting that a police report will be made available ‘if and when’ a person is charged in court.

Section 51A of the Criminal Procedure Code (CPC) is a newly inserted provision (2006) to govern what is known in criminal procedure as ‘disclosure’ requiring each side in a criminal proceeding to reveal information and disclose documents.

Prior to 2006, the general right to disclosure of documents was governed by section 51 of the CPC, which empowers the court to issue summons or an order to produce the property or document that is necessary or desirable for a trial. The section remains in force.

Section 51 has given rise to a number of conflicting decisions on the right of the accused to inspect documents and other prosecutorial materials. Suhakam in its report ‘Forum on the right to an expeditious and fair trial’ (2005) has duly noted the inadequacies in the disclosure regime which often resulted in adjournments and therefore delays.

As part of reforms to the criminal process, section 51A was inserted into the CPC. So clearly, section 51A of the CPC cannot be relied upon to deny a person his common law right to inspect a document in which he has an interest.

On a parting note, I find the following excerpts from the judgment of Syed Othman FJ in Husdi enlightening:

‘[S]upplying the arrested person with the first information has all the advantages to everyone concerned. It gives the accused person the first opportunity to explain. If his explanation is satisfactory, it may shorten investigation and cut down public expense.

‘Even if it is unsatisfactory, it will give the police officer better leads in his investigation.’

But if common sense does not prevail, perhaps the person making the FIR should voluntarily give the person or persons named in the FIR a copy of it – expenses to be paid, of course.

And may I add, ‘What is there to be afraid?’

Or should I say, ‘What is there to hide, if indeed the police report has been made?against Anwar is so lacking that DNA matching will be the main ’

Anwar has been accused of sodomy, which he denies, saying it is a politically motivated move to stop him challenging the government.

Anwar has been accused of sodomy, which he denies, saying it is a politically motivated move to stop him challenging the government. "I have submitted my resignation letter to the House speaker today," she said.

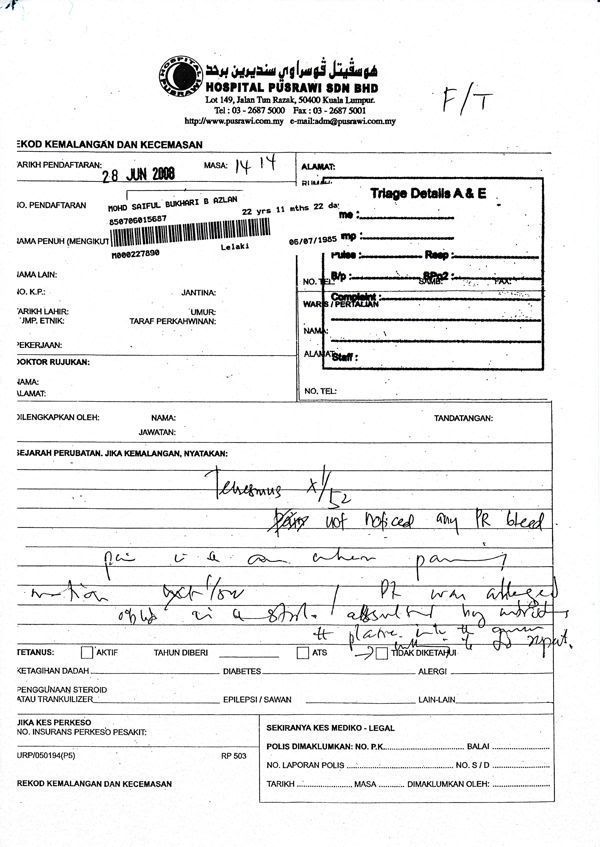

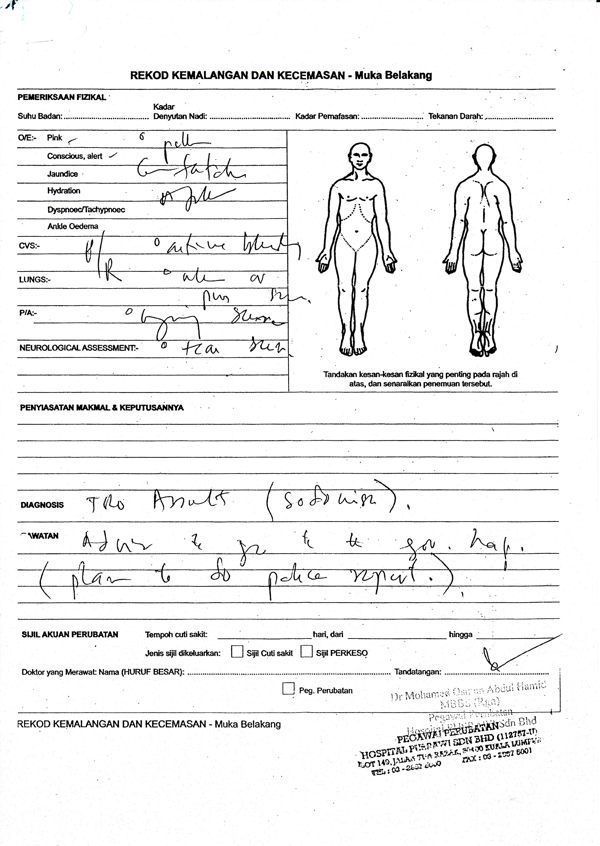

"I have submitted my resignation letter to the House speaker today," she said. Over 40 minutes, he told a packed press conference at the party's headquarters in Petaling Jaya this morning that the Hospital Pusrawi (Pusat Rawatan Islam) medical report on Saiful proved that his 23-year-old ex-aide was an "outright liar".

Over 40 minutes, he told a packed press conference at the party's headquarters in Petaling Jaya this morning that the Hospital Pusrawi (Pusat Rawatan Islam) medical report on Saiful proved that his 23-year-old ex-aide was an "outright liar". Anwar's lawyer, Sulaiman Abdullah (photo, far right) who was present at the press conference, described the police's immediate reaction to the medical report's release yesterday as "interesting" given that they did not questioned its authenticity.

Anwar's lawyer, Sulaiman Abdullah (photo, far right) who was present at the press conference, described the police's immediate reaction to the medical report's release yesterday as "interesting" given that they did not questioned its authenticity. Among those present today included Anwar's wife and PKR president Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail, PKR leaders Syed Husin Ali, Azmin Ali and Saifuddin Nasution Ismail, PAS leaders Kamaruddin Jaafar and Dr Hatta Ramli.

Among those present today included Anwar's wife and PKR president Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail, PKR leaders Syed Husin Ali, Azmin Ali and Saifuddin Nasution Ismail, PAS leaders Kamaruddin Jaafar and Dr Hatta Ramli. The Star quoted ministry director-general Dr Mohd Ismail Merican as saying this in response to the latest twist in the sodomy allegation against opposition stalwart Anwar Ibrahim.

The Star quoted ministry director-general Dr Mohd Ismail Merican as saying this in response to the latest twist in the sodomy allegation against opposition stalwart Anwar Ibrahim. "We want to solve this case as soon as possible. The investigating officer is constantly looking for new leads.

"We want to solve this case as soon as possible. The investigating officer is constantly looking for new leads.  While he conceded that Saiful had initially gone to Pusrawi before heading to Hospital Kuala Lumpur, he dismissed the initial findings, saying that Pusrawi "did not have a forensic department" of its own.

While he conceded that Saiful had initially gone to Pusrawi before heading to Hospital Kuala Lumpur, he dismissed the initial findings, saying that Pusrawi "did not have a forensic department" of its own. The 20-something youth then challenged the Malaysia Today editor to see him personally.

The 20-something youth then challenged the Malaysia Today editor to see him personally. The former Bar Council president (centre) was asked to comment on concerns expressed over the infringement of patient-doctor privacy with the leak of the medical report on Saiful.

The former Bar Council president (centre) was asked to comment on concerns expressed over the infringement of patient-doctor privacy with the leak of the medical report on Saiful.  The branches also took deputy inspector-general of police (DIGP) Ismail Omar to task for stating that media reports on the doctor’s findings were aimed at confusing the people.

The branches also took deputy inspector-general of police (DIGP) Ismail Omar to task for stating that media reports on the doctor’s findings were aimed at confusing the people. "I call upon them to do so as quickly as possible in order to clear the air over the case but the contents of the first medical examination to be revealed must be as originally written by the doctor who conducted the investigation," he said in a statement.

"I call upon them to do so as quickly as possible in order to clear the air over the case but the contents of the first medical examination to be revealed must be as originally written by the doctor who conducted the investigation," he said in a statement. "DAP will fully support Anwar's campaign to win the imminent by-election and earn his rightful place in the August House.

"DAP will fully support Anwar's campaign to win the imminent by-election and earn his rightful place in the August House. At a rally in the Malay-dominated industrial town of Kulim on Sunday, Anwar announced his intention to contest in the by-election if the Alor Star High Court decision on Aug 19 declared the seat vacant.

At a rally in the Malay-dominated industrial town of Kulim on Sunday, Anwar announced his intention to contest in the by-election if the Alor Star High Court decision on Aug 19 declared the seat vacant. Chief Minister Lim Guan Eng said his predecessor should emulate the example set by his former deputy by publicly admitting that he was responsible for land scams that have cost the state millions of ringgit.

Chief Minister Lim Guan Eng said his predecessor should emulate the example set by his former deputy by publicly admitting that he was responsible for land scams that have cost the state millions of ringgit.

However, Ezam conceded that his chances of winning as a Barisan Nasional (BN) candidate would be slim given the "political and economical" factors in the country at the moment.

However, Ezam conceded that his chances of winning as a Barisan Nasional (BN) candidate would be slim given the "political and economical" factors in the country at the moment. "No one in this world would have suffered and been humiliated like me. If I am wrong, I will put up my hands and surrender.

"No one in this world would have suffered and been humiliated like me. If I am wrong, I will put up my hands and surrender. He confirmed he had chosen Kulim –Bandar Baru to earn his right to be a parliamentarian after a 10-year hiatus because it is located close to his Penang hometown Cheruk Tokun.

He confirmed he had chosen Kulim –Bandar Baru to earn his right to be a parliamentarian after a 10-year hiatus because it is located close to his Penang hometown Cheruk Tokun. He said the federal government ban barring him within 5km distance from the Parliament when opposition leader Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail wanted to table a no-confidence vote against the premier was a clear sign that Umno leaders feared him.

He said the federal government ban barring him within 5km distance from the Parliament when opposition leader Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail wanted to table a no-confidence vote against the premier was a clear sign that Umno leaders feared him. It is believed that Anwar's former aide Saiful (left) went to two different hospitals on June 28 - the day he lodged the police report claiming that he was sodomised by his ex-boss.

It is believed that Anwar's former aide Saiful (left) went to two different hospitals on June 28 - the day he lodged the police report claiming that he was sodomised by his ex-boss. A senior Pusrawi official told malaysiakini this morning that the hospital had launched an internal investigation on how Saiful's medical report was leaked, which is widely considered as a major infringement of patient privacy.

A senior Pusrawi official told malaysiakini this morning that the hospital had launched an internal investigation on how Saiful's medical report was leaked, which is widely considered as a major infringement of patient privacy. At 6pm on that day, Saiful went to Hospital Kuala Lumpur for his second medical examination. He subsequently lodged a report against Anwar at the police beat at the hospital.

At 6pm on that day, Saiful went to Hospital Kuala Lumpur for his second medical examination. He subsequently lodged a report against Anwar at the police beat at the hospital. It is learnt that the police have recorded statements from Mohamed Osman after Saiful lodged the report against Anwar.

It is learnt that the police have recorded statements from Mohamed Osman after Saiful lodged the report against Anwar. Lance-corporal Shahrizan Abd Rashid (left), 25, who was at the scene on May 27 controlling the traffic, said he saw Chang’s Proton Wira speeding towards him and a group of policemen.

Lance-corporal Shahrizan Abd Rashid (left), 25, who was at the scene on May 27 controlling the traffic, said he saw Chang’s Proton Wira speeding towards him and a group of policemen. Following this, he said CID and FRU personnel stationed at the scene moved in and arrested Chang.

Following this, he said CID and FRU personnel stationed at the scene moved in and arrested Chang. The inquiry panel is headed by commissioner Zaiton Othman, and includes commissioners Dr Chiam Heng Keng and Khalid Ibrahim.

The inquiry panel is headed by commissioner Zaiton Othman, and includes commissioners Dr Chiam Heng Keng and Khalid Ibrahim.